News this week that for the first time more women are applying for jobs in financial and professional services than men. That’s great, of course, but getting women into the professions isn’t the problem. Keeping them is the challenge.

Writing Out of the Doll’s House 25 years ago, I was optimistic. By 2014 women judges, CEOs, senior partners would be so commonplace we’d no longer be talking about a glass ceiling. The surge of women into the professions in the 70s and 80s would create a pipeline of brilliant women who would surely provide an irresistible pool of talent from which leaders would be chosen.

I was wrong. That pipeline turned out to be very leaky. As men rose through the ranks, women more often moved out than up. The pool of women for top jobs is small and they are still a rarity. The figures are familiar – one woman in the Supreme Court, four women CEOs in the FTSE 100 and less than a fifth of equity partners in leading law firms. With more family-friendly initiatives around than when we baby boomers were working mums, this is not only disappointing but surprising.

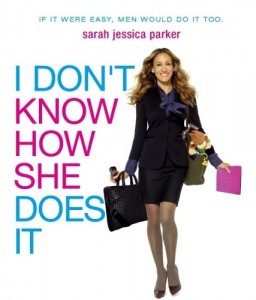

Professional women today have as tough and in some ways a tougher time juggling work and family than we did. These days there is less talk of breaking glass ceilings, instead academics use the phrase finding ‘a route through the labyrinth’. Mothers (not childless women or those with house-husbands) face a series of obstacles blocking their paths.

First, working life for many professionals has speeded up dramatically in the last 30 years. Hillary Clinton’s State Department was thought lenient for only requiring executives to be in the office eleven hours a day, a work ethos that has spread over here and is familiar to many, particularly in finance and law, who count themselves, lucky to get home by 9pm and escape all-nighters. It’s an almost impossible call for a mother who has to collect children from a nursery or take over from a child-minder.

And here lies the second problem. It is still usually mothers. While employers may have come round to accepting the need to make a few concessions for motherhood, it’s far harder for an enthusiastic father to plead parental responsibilities. In the corporate world if he doesn’t put in the hours in the office, he isn’t taken seriously. So despite willingness to share (an improvement on men of my generation) women are still usually the ones racing home to put children to bed and cook the dinner, often returning to their laptops late into the night.

Women today are also disadvantaged by the cult of rapid achievement – an expectation that you must make the grade by a certain age. This conflicts with time off for maternity leave and, as it is common for professional women to put off having children until their mid or late 30s, the big push for seniority often coincides with the greatest demands from family life.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle of all is childcare. UK childcare is the second most expensive in the world, higher even than the US. A full-time nursery place in London can be as much as £22,000 a year and the cost of a professional nanny is considerably higher. Live-in help is only possible in the size of house unaffordable for many in today’s market and finding a registered child-minder is difficult as numbers have halved since the mid-90s due to the cost of training and insurance.

The combination of escalating child-care costs and the rigidity of the corporate culture makes it hard for today’s working mums to stick in there. All power to organisations like Women on Boards and the 30% Club who are trying to encourage and support them.