A shorter version of this appeared in The Times, May 3 2012

VOTE THE RASCALS IN

The mayoral candidate exploded with fury in a foul-mouthed tirade. No, not the recent spat between Boris and Ken but Norman Mailer in 1969. The summer of Woodstock, Chappaquiddick and the moon landings, saw Norman Mailer, Pulitzer prizewinning author and journalist, running for Mayor of New York. The Boris and Ken show is tame by comparison. As manager of his campaign headquarters, I was at Mailer’s first major fund-raiser. He turned on his audience of volunteers and donors, drunkenly punctuating his speech with ‘Fuck yous’, telling us we were, ‘a bunch of spoiled pigs … sitting around jerkin’off, havin’ your jokes … and more than that you all want to work for us? You get in there, and you do your discipline and you do your devotion … Don’t come in there and help us because ‘we’re gonna give Norm a little help’. Fuck you.’

It wasn’t the best way to inspire supporters in what was arguably one of the most provocative and colourful campaigns New York has ever seen.

It all began on an April evening at Norman Mailer’s house with a bunch of New York’s finest – journalists, novelists, polemicists of all sorts – throwing ideas around on how to transform the city. The Democratic Primary for mayor was but a few months away and with Mailer leading the crusade, they believed they had a libertarian vision which would draw from right and left, cutting across traditional political lines. The big idea was to liberate New York City and turn it into the fifty-first US state. New Yorkers paid $22 billion in income tax to the federal government and only got back around $6 billion. Mailer proposed they kept the lot. Decentralisation didn’t stop there. Individual neighbourhoods would govern themselves. Harlem and Staten Island, for instance, could declare themselves townships and do their own thing. The emphasis was on community. Someone on welfare would be given the task of beautifying the area he lived in, while getting job-training on house restoration, the same thing with offenders. Anyone with a stake in the community, it was assumed, wouldn’t want to trash or rob it.

New Yorkers liked the idea of holding the purse strings and stopping farmers upstate grabbing the city’s money but they were less impressed by some of Mailer’s other ideas. Most controversially, he called for the legalisation of heroin to cut drug-related crime and be made available rather like methadone is here. He wanted a ban on private cars in Manhattan, free public transport and (40 years before Boris) city bikes. This, he said, would reduce pollution by three-fifths. He planned to increase the number of cabs, and encourage cab-sharing schemes. Apart from taxi drivers, no one was very enthusiastic. There were mutterings about joy riders on the subway and biking muggers swooping down on innocent shoppers in Fifth Avenue.

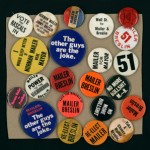

The idea people found the hardest to grasp was Sweet Sunday. The last Sunday of every month the city would come to a halt in a kind of biblical way to ‘cleanse itself’. For 24 hours nothing but emergency services would be allowed to move. There would be no planes, trains or cars. People would talk to their neighbours, rest and play while the air around them grew pure. New Yorkers didn’t get it. It was obviously just a big joke. Lapel badges saying ‘No More Bullshit, Mailer for Mayor,’ and ‘Throw the Rascals In’ reinforced this suspicion.

But Mailer was deadly serious. He wanted to win. His ideas, he conceded, were ahead of their time, but he had a high-profile, he was a prominent writer attracting a huge amount of press coverage and his running-mate, the journalist Jimmy Breslin, was a much-loved New York character. The problem was that even if he had thrown out some of his dottier ideas, he was surrounded by people like himself who enjoyed debating policy but had little interest in the dull logistics that make a successful campaign. Little thought had been given to canvassing, budgeting, fund-raising, even banking donations. At the end of each day, I went home to one of the dodgier parts of the city with wads of dollars stuffed in my bra which I hid in a cushion until someone eventually decided what I should do with them.

No one had worked out how to use the volunteers who turned up in their dozens to work on the campaign. Mailer’s ideas appealed to the young and the New Left. Activists who had worked for Eugene McCarthy in his presidential bid the year before enthusiastically offered their unpaid services only to be told there was nothing for them to do and to come back next week. The campaign manager, Joe Flaherty, a columnist on the Village Voice, had his work cut out managing Mailer. He left the campaign to run itself. The fact that, as a 22-year old British student, I was let loose to manage the Manhattan headquarters underlines the point.

Mailer, himself, never quite saw the need for volunteers. He grumbled that the ‘fuckin’ beards and leftists’ were lowering the tone. He fretted that the campaign was over-run by hippies. It was certainly true that the he was the hip choice for mayor, the hippies being the only ones who ever truly believed in Sweet Sunday, and that campaign cars were brightly coloured with psychedelic symbols, but there were few, if any, actually working on the campaign. On his rare trips to headquarters, he eyed us suspiciously, giving those he recognised an imaginary boxing punch. In the final weeks of the campaign, he demanded a loyalty test. Beards and moustaches had to go, hair to be cut short. This divided the staff into two camps – the loyalists and the refuseniks (including Campaign Manager, Joe Flaherty). The two sides stopped speaking to each other.

Mailer, who drank heavily throughout the campaign, rose above all this. He thought if he stood at subway entrances in the early morning, walked around the city during the daylight hours and addressed selected groups in the evening that would be enough. ‘The difference between me and the other candidates’, he said, ‘is that I’m good and I can prove it.’ At his best he was an impassioned and impressive speaker but Mailer, who had no trouble unbending in a bar, could seem stiff, even awkward meeting and greeting in the street. New Yorkers were largely unimpressed. His ideas were too wacky, his campaign too anarchic.

On election night he took a suite in the Plaza surrounded by a strange coterie of writers and fellow drinkers, including all 460 pounds of Jimmy Breslin’s bookmaker friend, Fats Thomas. Like many outsiders before and since, he’d convinced himself he was in with a chance. He watched the results filling the TV screens with increasing gloom. He was fourth out of five. The winner of the Democratic primary, Mario Procaccino, dismissed by Mailer (‘I can’t get a grasp on a mind this small’) was later beaten by the incumbent Republican, John Lindsay.

In statistics, an outlier is a sample that lies outside the expected range of possibilities. As political candidates go Norman Mailer was clearly an outlier, but such candidates occasionally win. In recent years at opposite ends of the political spectrum Barack Obama and George Galloway have defied the odds. They had ideas that resonated with their constituents and the organisation to carry it through. Mailer’s quixotic campaign had neither.